How Artists’ Books Live

by Heather Jones

Leading up to the 10th edition of the Bergen Art Book Fair, taking place April 14-16 in Bergen Kunsthall, I have been invited to moderate a conversation with a group of independent publishers on the current state of artists' books and the roles that bookstores and art book fairs play in supporting the genre. The below text serves as a brief overview of publishing as artistic format in the US and Europe, looks at the challenges facing artists and publishers today, highlights the crucial role of art book stores and fairs, and considers the enduring appeal of artists' books.

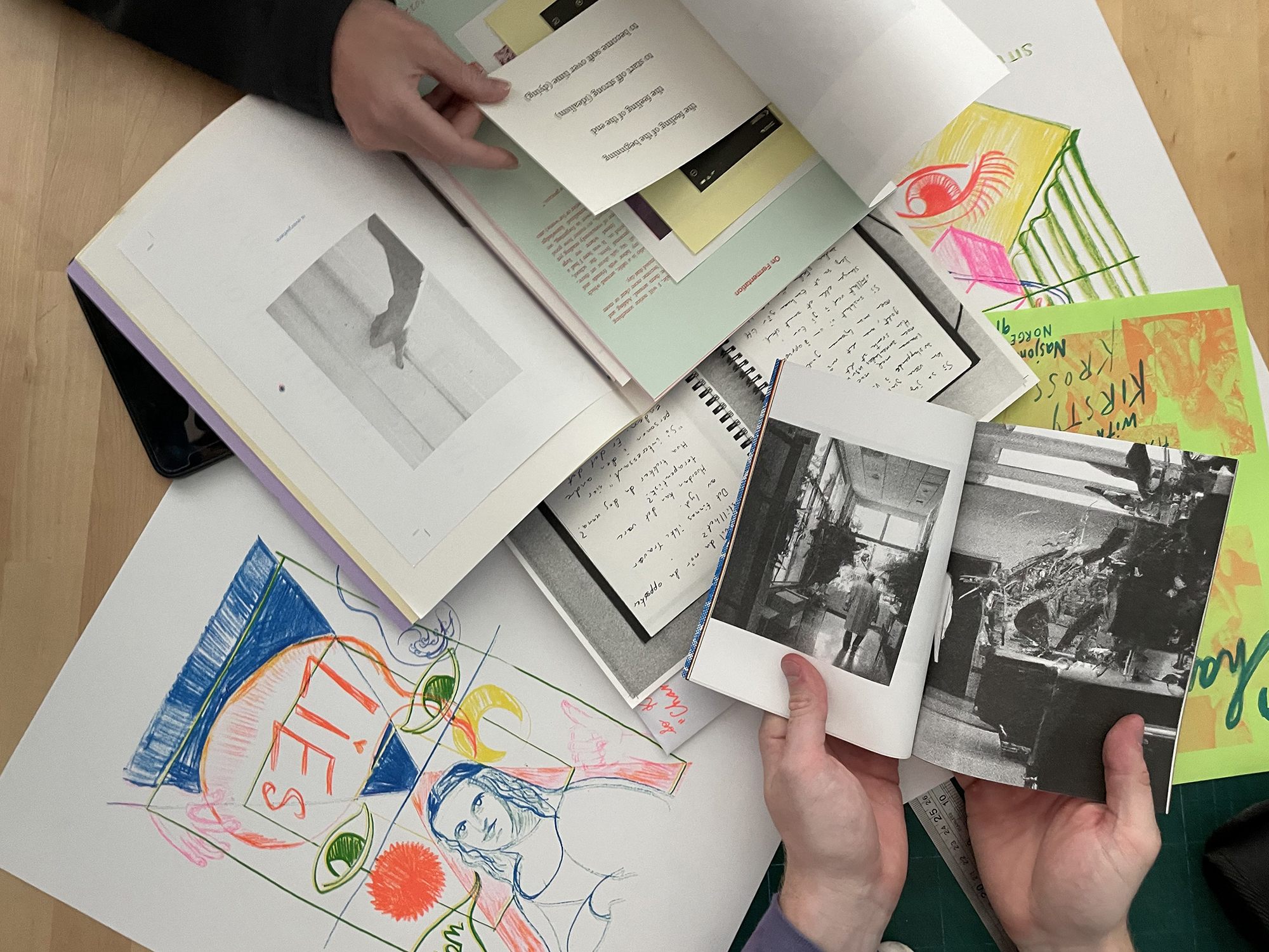

Kunstbokhandel Under Press (2023). Photo: Mario de la Ossa.

Kunstbokhandel Under Press (2023). Photo: Mario de la Ossa.

Art Books from Europe in Beijing

I was recently speaking with an artist based in Stavanger about a project she is currently working on – an artist book in the form of a deck of cards with an accompanying booklet, or maybe it will become a poster, a poetic text related to a previous video work… anyway, while discussing, we momentarily fell into the morass of trying to define what an artist book is, how it is differentiated from a limited edition (if at all), and how best her project could be defined. As we attempted to tease apart the differences, I realized how little I actually knew about artists’ books despite coming into contact with them on a fairly regular basis. What are artists’ books and how would I describe them to another person? Printed Matter Inc., one of the founding spaces of the artist book movement and reigning titan, defines artists’ books as:

“Unlike an art book, catalog or monograph that tend to showcase artworks created in another medium, the term ‘artists’ books’ refers to publications that have been conceived as artworks in their own right. These ‘projects for the page’ are generally inexpensive, often produced in large or open editions, and are democratically available.” Printed Matter

Picnic in Los Angeles with David Horvitz (Edition Taube)

Generally… but not always. In reality, no strict guidelines exist for what may be defined as an artist book. The field is extremely heterogeneous. Several years ago, I audibly gasped at the price of a unique, gold leaf artist book, kept locked behind glass and secured with its own guard at the New York Art Book Fair. Just last month I was in awe of the experimentation that The Book Art Museum in Łódź encouraged in the format. I have seen collections of CDs, tapes, and curated digital files described as artists’ books. I have encountered boxes and folders of printed matter, foldouts and concertinas, bound pages, loose pages, hardcovers, softcovers, folios and scrolls, posters, postcards and zines, unique artworks, sales tags as books, and books as sculpture, and a dot-matrix printer that printed out material for visitors on demand. I have seen a gargantuan book mounted to a wall, and books small enough to fit in a matchbox (this edition came with an adorable little magnifying glass).

The content of artists’ books has included texts, manifestos, poems, personal letters, photography, drawing, musical scores, instructions for performances, documentation of happenings, maps, and blank pages. They exist in widely circulating editions, limited editions, or as singular unique objects. They can be made from cheap, readily available materials like newsprint and cardboard, or painstakingly handcrafted with vellum and jewel-toned ink. They may be constructed from paper, leather, textile, metal, plastic and any other material imaginable. Artists’ books are created on fine printing presses, affordably mass-produced on risograph printers or photocopiers, and/or digitally available online.

Hverdag Books

I took a cue from the Printed Matter Inc.’s strategy of defining artist’s books by placing them in contrast to what they are not. They are not monographs, or art books, or catalogues. They are not magazines or newspapers, narrative literature or historical documentation. But they could, and do, occasionally take all of these formats. I tried to make a list of things an artist book is not, or could not be, and came up empty. An erotic novel – I’ve seen it done. A grocery list – done. Political treatise or news report – done. A sculpture, a playlist, an instruction manual – done, done, done. With a field this broad, I wonder if a clear definition of the term ‘artist book’ is even possible. And it’s not just me who is confused. Existing scholarship on artists’ books does not always agree – nor do the artists and publishers that produce them. In his book Artists' Books: The Book As a Work of Art, 1963–1995, art historian Stephen Bury offers the following definition: “Artists' books are books or book-like objects over the final appearance of which an artist has had a high degree of control; where the book is intended as a work of art in itself.”1 According to Bury, it’s not the format or content, but the intention that defines the genre. Following this logic, if a creator decides something is an artist’s book at its inception, then it is.

But even the term “artist book” itself is under fire. I have seen this field referred to as art books, artists’ books, artistic publishing, publishing as artistic practice, and (my personal favorite) art in book form. Lawrence Weiner once famously simplified the matter by saying: “Don’t call it an artist’s book, just call it a book.”2 However artist and writer Michalis Pichler suggests that it is the term “book” itself that is the problem. He suggests that we do away with the term altogether noting, “today, we are no longer only talking about books anymore—more capacious than book, the term publication is better because it can encompass digital files, hybrid media, and forms we have yet to imagine.”3

As you dig into the discourse on the subject of artists’ books, it becomes apparent almost immediately that the definition of the artist book, or lack there of, is perhaps the most prominent disagreement within the genre. Artists’ books are less of a clearly delineated art form and more of a hazy Venn diagram of artistically intentioned printed matter. It’s frustrating, but perhaps the irritating indefinability of the genre is also its strength.

New York Art Book Fair, Printed Matter

As I was writing the above, I remembered one of my first, and probably most intimate experiences with an artist book. A then-boyfriend(ish) of mine was working on a beautiful book of writing and photographs, with bits and pieces tacked all over his tiny bedroom/studio. When I asked him why this should all be a book, instead of an exhibition, he succinctly responded, “so that I can close it.” This statement is cheesy. But it got me thinking less about what an artist book is, and more interestingly about what it does. How do artists’ books function in the world differently than other artworks?

To dig into this question, let’s circle back to the birth of the artist book as we know it today. Of course artists have been engaged in printing processes and book production for centuries, but the term ‘artist book’ mainly refers to works created from the mid-20th century onwards. The practice of artistic publishing grew, at least in part, out of the turmoil of World War II and the desire to forge communities of like-minded individuals that transcended the boundaries of warring nation-states. In terms of self-identification, shared ideals trumped national citizenship, and artists’ books offered a new, non-hierarchical model for the production and distribution of art and ideas, and thus the format was adopted across genres.

Many groundbreaking artists of the 1960s further developed the format of the artist book, recognizing its high-edition, low-cost format as an ideal site for experimentation outside of the established gallery system. The artist book’s financial accessibility and physical portability gave rise to the increased production of printed matter throughout the 1960s and 70s, in correlation with a wide-spread surge of socio-political activism. Furthermore, technological advances at the time enabled artists and writers to seize the means of production, freeing their creative processes from the constrictions of galleries, museums, editors, and publishing houses.

“It was at this time that a number of artist-driven alternatives began to develop to accommodate a new forum and arena for all those artists who were denied access to the traditional galleries and museums. Independent art publications were one of these options and artists' books became part of this throng of experimental art forms.”

Johanna Drucker, The Century of Artists' Books, Granary Books, p.72.

It didn’t take long for the institutions to take notice of the burgeoning art form. In 1972, London’s Nigel Greenwood Gallery organized the first international exhibition of artists’ books titled, Book as Artwork, 1960/72.4

This was closely followed by the 1973 exhibition of artists’ books at Moore College of Art in Philadelphia, in whose printed catalogue the term ‘artists’ books’ was coined. At this point it would seem that the new, experimental, non-hierarchical art form had been smoothly co-opted back into the art world establishment, but that would be an oversimplification. The format itself fights back. While artists’ books certainly exist within gallery and museum settings, their intimate viewing requirements, (usually) low cost and high edition generally do not make for profitable exhibitions. However it was recognized that artists’ books, and the community surrounding them, would benefit from a slightly more formal structure of support.

The mid-late 1970s hosted a proliferation of art bookstores and organizations dedicated to the furthering of the format. Art Metropol in Toronto was founded in 1974 by the collective General Idea as a nonprofit art space focusing on “contemporary art in formats predisposed to circulation and dissemination: artists’ books and art publications, video, audio, electronic media, and multiples.”5 The same year, the Center for Book Arts opened in New York with the mission of promoting ‘book arts’ through “education, preservation, exhibition, generation, and community building.6

1976 saw the birth of Printed Matter Inc., a juggernaut of the artist book community. It was founded in Tribeca by a group of artists including Lucy Lippard and Sol LeWitt in response to a growing interest in and need for a physical space that highlighted art in book form. Printed Matter Inc. was, and continues to be, a key player in increasing this visibility and understanding of artists’ books as complex artworks in their own right. As of today, it is the predominant non-profit artist book organization in the world, and is committed to the “dissemination, understanding and appreciation of artists’ books and related publications.”7

Across the ocean other spaces also emerged. Book Works was founded in London in 1984 with a commitment to enhancing artists’ books as an art form. Their studio and publishing activities have since been instrumental in enabling experimentation within the field. In 1986, Boekie Woekie was founded by a collective of six artists in downtown Amsterdam as a way to highlight their own works and slowly growing over the resulting years to include artists’ books by an increasing variety of international artists. They are one of Europe’s oldest spaces dedicated to artists working in book format, regardless of the author/artist’s notoriety. And in 1998, Christoph Keller founded Revolver Verlag in Berlin (then called Revolver Archiv für aktuelle Kunst), publishing a wide variety of content including special edition artworks, catalogues, works of philosophy and theory, all in relation to art, architecture and design. They have supported the careers of acclaimed artists such as Francis Alÿs, Candice Breitz, Christian Jankowski, Hassan Khan, and Nasan Tur.

Although artists’ books and organizations had been garnering attention worldwide since the 1970s, this artistic format did not have the same level of support here in Norway. Torpedo was founded in Oslo in 2005 in response to the closing of the bookshop at Museet for Samtidskunst. Torpedo is a “non-profit Bookshop and Publisher devoted to the promotion and production of artists' publications, art theory and critical readers.” Interestingly, they openly cite Art Metropol and Printed Matter Inc. as inspiration for the organization’s founding. The bookshop and publishing house has grown to include Nordic Art Press (2017) in an effort to develop a better distribution platform for artists’ books. In 2011 the first "fanzine nights" were organized in Bergen by the people behind Pamflett (2013), which later grew into a self-publishing workshop and mediation space for artists’ publications, and a leader in the printing technique of risography in Norway. In 2013 Pamflett organized the first Bergen Art Book Fair, which has become the Nordic region's largest and longest-running art book fair. In Tromsø, Mondo Books (2007) established itself not only as a book publisher, but also as a research platform for projects related to printed matter and social movements, with a focus on the Barents region. They organized the first Arctic Art Book Fair in 2020 and are committed to supporting content from the arctic region, stating a focus on "indigenous perspectives, under-represented voices and cross-border collaborations."8

Bergen Art Book Fair 2022

Other art book initiatives have found havens within larger art institutions. In 2009, the artist collective and literature organization House of Foundation opened in Møllebyen, Moss, and included the Audiatur bokhandel (bookshop) from which sprang the publishing house H//O//F. The small, niche bookstore Babel Bok exists within the artist-run contemporary art space BABEL visningsrom for kunst, and the specialty art book store Kunstbokhandelen B*stard, one of the current largest outlets for artists' books within Norway, physically lives within the walls of Oppland Kunstsenter in Lillehammer.

And on and on and on. The global proliferation of publishers and bookshops focusing on the production, exhibition, and distribution of artists books has increased exponentially in Europe: Konst-ig (Stockholm, 1994), Edition Taube (Munich, 2009), Yvon Lambert (Paris, 2017), MATERIAL (Zurich, 2017), Lodret Vandret (Copenhagen/Berlin, 2010), Good Press (Glasgow, 2011), Hverdag Books (Moss, 2016), and most recently the temporary initiative Kunstbokhandel Under Press (Entrée, Bergen, 2023)…The list in endless and ever evolving. It’s obvious that, despite the blurred definition of artists’ books, the phenomenon of the format is waxing rather than waning. The proliferation of stores dedicated to artists’ books (and for that matter artists’ book themselves) is understandable in the pre-internet era. But why has interest in this format not only been maintained, but exponentially grown since its inception?

MATERIAL, Zurich

Many reasons have been given for the ongoing relevance of artists’ books. They are often the first artworks that young collectors can afford. The individual and intimate interactions necessitated by the book format create a more personal relationship between the viewer and the artwork. Printed Matter Inc. puts it well: “Much like any act of reading, an artists’ book is a physical experience that allows a connection with the medium that – while social in its implications – is individual and personal.” 9 Their cost efficiency and lack of “preciousness” creates a low threshold to entry and makes this format more accessible than almost any other. Quite literally, artists’ books are art that we can take with us. They are art with which we can live and interact on a daily basis: in our homes, at cafés, in cars, buses and trains, while waiting in interminable lines at the post office or on hold with the bank. It is art that I’m not (usually) terrified my toddler will ruin.

From the viewpoint of the artist, publications and books’ practical size and ease of production level the playing field, creating an inclusive way to spread individual practices and group philosophies. This medium allows an artist to disseminate their work to a broad audience across space and time. Printed Matter Inc., again: “It is this potential to reach a larger audience that lends the book its social qualities and increases its political possibilities. In this way, the artists’ book can be an incredibly powerful communicative force.”10

Further, the infinite possibilities of content, the wide variety of printing processes and book design all encourage experimentation in a way that is specific to the format of a publication. According to many practitioners, the low cost and ease of replication enables the work to exist largely outside of the capitalist constraints of the mainstream art market. Artists’ books seek to bypass the traditional cultural gatekeepers and return art, quite literally, into the hands of the people.

And while all of that may be true, the phrase “exists outside the capitalist system” is often a euphemism for “doesn’t make any money.” Despite its ideals, the artist book industry is an industry, and as such it faces many challenges for survival. In a questionnaire on the current state of art book publishing (initiated by Pamflett and Entrée in relation to their current project Kunstbokhandel Under Press), financial viability was overwhelmingly listed as the #1 challenge.* There are several factors that contribute to this lack of market solvency.

Many of the makers and publishers of artists’ books are artists themselves, and not always able or willing to balance their creative output with the administrative tasks needed to produce a profit. In one example, Lodret Vandret, which also runs the art book festival One Thousand Books in Copenhagen, notes that as makers, they are not as comfortable in the role of salesmen of their own work.

One Thousand Books 2018 at Annual Report

One Thousand Books 2018 at Annual Report

Norwegian artist book publishers Torpedo and Hverdag Books both cite underrepresentation and the lack of a more mainstream audience as critical weak points in the field. While the artist book community is a thriving one, there is decidedly less visibility, writing, funding, and collecting of artists’ books on the same scale as other forms of artwork. Therefore publishers of artists’ books are forced into the role of educator/lobbyist in addition to their existing work as creators, publishers, marketers, and distributors.

The reception of artists’ books within the mainstream art world also leaves much to be desired. Despite the 70+ years of the art form’s existence, the disparity between the vibrancy of the field of artistic publishing and the critical discourse around it is glaring. Although critical research projects, publications and articles on the subject of artists’ books do exist, the scholarship nowhere near reflects the amount of output in the field. This lack of visibility directly impacts the funding of these initiatives. The amount of financial support for the publishing of artists’ books is significantly lower than that of other art forms. While the material cost of publishing these books often remains low according to the ethos, the cost of labor should not. Furthermore, funding for individual projects may be attainable but it is extremely rare for a publisher of artists’ books to receive funding for ongoing operational costs. Many small publishers can only afford to hire staff part-time, and others, like Bladr and MATERIAL, are run entirely by members and volunteers. This, in turn, effects the amount of time that they can spend marketing and selling their books, which then effects their ability to pay for their labor… and around goes the carousel.

Marketing and distribution of artists’ books is another widely cited challenge facing the field. While more established initiatives manage to sell online and link with other international distributors, many smaller publishers and book stores lack the framework to efficiently distribute books via the internet, track payment and delivery fulfillment, and follow-up on commissions. Additionally, due to the lack of perception of artists’ books as works of art (and most likely the books’ minimal cost), many commissioners of artists’ books such as bookstores and museum shops do not prioritize the selling, payment, and tracking of books in their selection. Most, if not all, artist book publishers use their websites, social media and newsletters for the marketing of their books, but many admit that this results in very few sales. Rather, they use these digital platforms as teasers for what could be experienced in their shops in real life. Lodret Vandret notes that analogue platforms are preferable and more effective as “newsletters are not opened anymore, and Meta’s algorithm would like us to pay for promotion.”

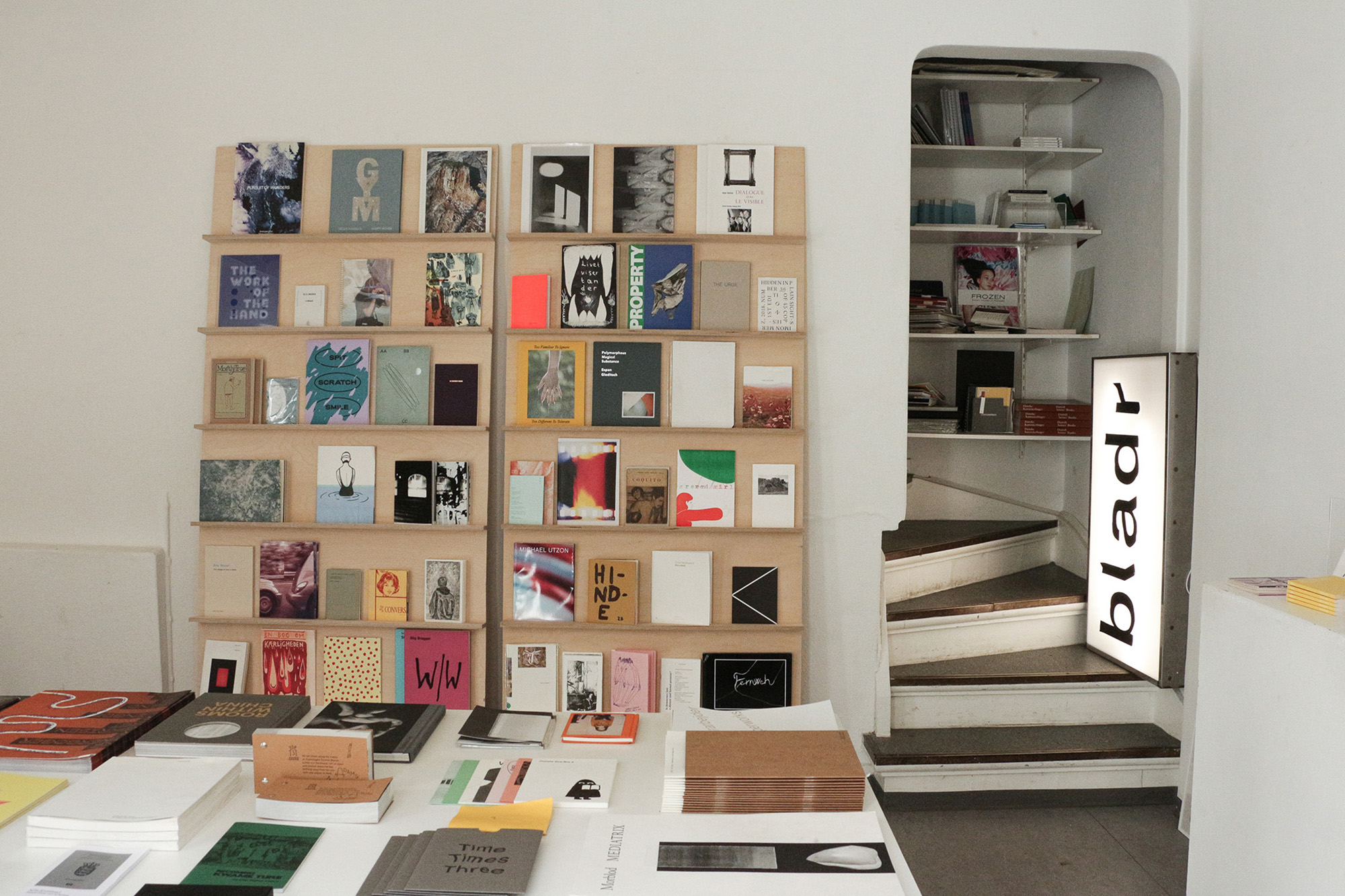

Bladr, Copenhagen

To sum it up, a lack of acknowledgement and mediation of artists’ books as a legitimate art form and the resulting lack of discourse, funding, representation, and collection on the part of the larger art community trickles down into less efficient distribution and payment systems, with unsold books even getting lost, forgotten on shelves, or accidentally donated. And since artists’ books are often not considered art, their creators (artists!) rarely receive the same level of financial support offered to artists working in other media. Perhaps the biggest challenge, then, is balancing the philosophies embodied in the artist book movement with the realities of staying afloat in the current capitalist financial system. This, I believe, is where art book fairs step forward to bridge the idealistic aspects of the book art community while also offering an integral solution to the challenges of mediation, marketing and distribution to a broader audience.

Nearly all publishers that responded to the questionnaire by Pamflett and Entrée listed art book fairs and festivals as the single most important venue for the marketing and distribution of their work. They are essentially a temporary, centralized collection of pop-up bookshops. In 2004, Printed Matter Inc. founded the New York Art Book Fair (and later the Los Angeles Art Book Fair in 2013). It remains the world’s largest event highlighting the genre, with thousands of exhibitors flocking to New York every year from dozens of countries across the globe, and an estimated 39,000 visitors annually attend the event. In addition to individual sales tables, the NYABF hosts a myriad of events, panel discussions, book launches, concerts, workshops, and anything else you can imagine related to artists’ books. As Valentina Di Liscia put it in her reporting on the 2022 art book fair, “It’s a whole scene.” 11

Hverdag Books at Reykjavik Art Book Fair 2023

Using the NYABF as a blueprint, book fairs have cropped up in every major city, from London (Small Publishers Fair, 2022) to Tokyo (Tokyo Art Book Fair, 2009) to Berlin (Miss Read, 2009) to Johannesburg (Jozi Book Fair, 2009) Kuala Lumpur (KL Art Book Fair, 2021), and of course closer to home we have the Bergen Art Book Fair (2013). Many other book fairs have also popped up nationally in the years since, including the Trondheim Art Book Fair (2020), Arctic Art Book Fair (2020), Bastard Kunstbokmesse (2017) and Sinsen Art Book Fair (2022). In his 2019 article Art Book Fairs as Public Spheres, Michalis Pichler notes the rise of art book fairs as an entity in of themselves worth studying:

“Even if the buzz of interest in publication as an art practice around the turn of the twenty-first century resembles the hype around the “artist’s book” in the 1970s, the phenomenon of art book fairs in this quantity and intensity is something new. (...) Art book fairs today are not only a venue for representing a separate, prior publishing scene, they are also a central forum for constituting and nurturing a community around publishing as artistic practice.”

Michalis Pichler, "Art Book Fairs as Public Spheres", mitpress.mit.edu., (25 March 2019).

Book fairs are a whole scene – and yet I would argue that the fanfare is not without reason. These kinds of fairs not only sell books, but also generate awareness in the wider public about the art form. You might come for a concert and spend hours flipping through Japanese zines or listening to a talk by an artist collective you were previously unaware of. Although commercial, these book fairs are also social places that actively circulate knowledge and build community between practitioners and audiences. The drive behind artists’ books, at its root, is an idealistic one. The practice embodies an insistence on the physical and the relatively non-commercial in a world dominated by digital information and markets, and yet relies on these markets for financial survival. Art book fairs manage to funnel much needed financial support to small publishers of artists’ books while prioritizing the fostering of a truly international creative community.

The overwhelmingly noted importance of fairs and physical bookshops begins to answer my earlier query as to why artists’ books are still so popular, despite the long list of challenges. All of the above reasoning makes sense when I think about artists’ books from 1960s-early 2000s. They’re affordable to make and purchase, they circumvent institutional authority and support social and political action, they encourage experimentation, they’re easy to physically distribute, etc. But all of this could be said of the internet as well. In our digital era, information flows freely, e-books and pdfs are easily emailed and downloaded. We have websites and social media and audio and video and flashy animations and pings and pongs of all kinds. What do artists’ books offer us that our ever-present screens do not? On its website, Printed Matter Inc. suggests that it is the abundance of digital media that is in fact driving more and more people to seek the physicality reality of artists’ books.

“In the face of the ongoing proliferation of digital media and information, there has been an astounding resurgence over the past several years in both artists’ publishing and public interest.”

Printed Matter

I have to agree, and posit that the attraction of artists’ books lies in their sheer tactility that returns us to ourselves. The utter lack of attention grabbing ploys gifts back to us our agency, our attention, and our physicality in relationship to an artwork. And they do this in an accessible format that we can experience privately, outside of an art museum. We can feel their pages, glossy or textured, balance their weight, press our noses into the pages and inhale paper, ink, wax, and other aromas of production. In short, artists’ books are artworks that not only naturally integrate into the quotidian lives of their holders, but also directly affect the mentality – and mental health – of the people that choose to engage with them. To me, artists’ books are hopeful reminders that the physical world has not entirely lost its allure or its battle with the metaverse. Once again, it’s not only the content of the books that captures us, but what they do, how they encourage us to interact with them, the world around us, and each other.

MATERIAL, Zurich

* In January 2023, Kunstbokhandel Under Press (run by Pamflett and Entrée) sent out a questionnaire for independent publishers and art book stores for mapping common issues and challenges that could be a starting point for a continued dialogue and themes leading up to the Bergen Art Book Fair 2023 conversations series. The questionnaire received replies from Johan Rosenmunthe from Lodret Vandret and One Thousand Books, Sara Lubich from Bladr, Jan Steinbach representing roles in Edition Taube, MATERIAL, CVBOOKS at Cabaret Voltaire and edcat.net, Elin Maria Olaussen, Karen Christine Tandberg and Kim Svensson from Torpedo forlag and Nordic Art Press, Jessica Williams from Hverdag Books, and Matthew Walkerdine from Good Press.

FOOTNOTES

1) Stephen Bury, Artists' Books: The Book As a Work of Art, 1963–1995, Scolar Press, 1995.

2) Dieter Schwarz, Lawrence Weiner : books, 1968–1989: catalogue raisonné, p.120.

3) Michalis Pichler, "Artist’s Book as a Term Is Problematic", 3am Magazine (online). https://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/artists-book-as-a-term-is-problematic/

4) Germano Celant, Book as Artwork 1960-1972, exhibition catalogue, 6 Decades Books; 2nd edition, 2011.

5) https://artmetropole.com/about

6) https://artmetropole.com/about

7) https://www.printedmatter.org/about

8) https://mondobooks.no/about

9) https://www.printedmatter.org/about/artist-book

10) https://www.printedmatter.org/about/artist-book

11) https://hyperallergic.com/769888/the-ny-art-book-fair-is-a-whole-scene/