Magnhild Øen Nordahl

The Frisbee Perspective

Sogn og Fjordane Kunstmuseum

—part of Vestlandsutstillingen 2018

Curated by Randi Grov Berger

—part of Vestlandsutstillingen 2018

Curated by Randi Grov Berger

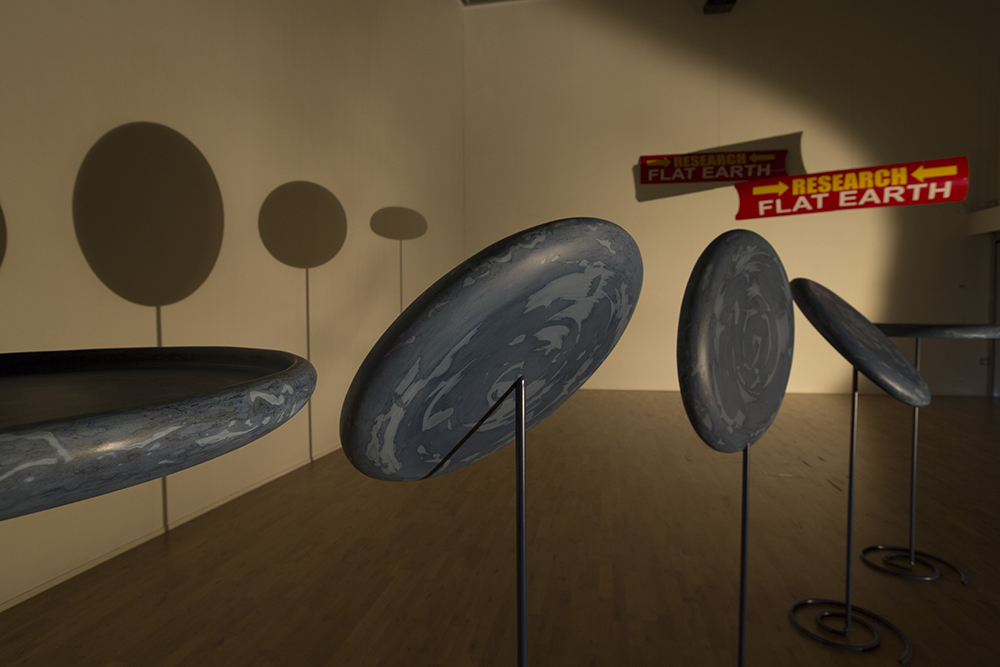

Installation view, The Frisbee Perspective. All images by Maya Økland/Vestlandsutstillingen.

In the exhibition The Frisbee Perspective Magnhild Øen Nordahl departs from two expeditions undertaken to investigate the shape of the earth. In the first, inspired by Nordahl's long-standing interest in the physical experience of scientific and geometric phenomena, the artist set off in a boat and traveled towards the horizon. Having calculated how far one can see before the curvature of the earth cuts off vision, Nordahl documented her journey to this point. This journey is re-staged for the viewer in the video The Distance to the Horizon. The second expedition was carried out by inventor and stuntman Mad Mike Hughes in the California desert in March 2018 when Hughes launched himself 500 meters into the air in home-made rocket. The launch was part of a series of stunts through which Hughes tries to prove empirically that the earth is flat, or, more precisely, shaped like a frisbee.

Magnhild Øen Nordahl (b. 1985, Ulstein, Norway) lives and works in Bergen, Norway, and was educated from the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm, Sweden and Bergen Academy of Art and Design. Through working with sculpture, installation and video, she examines dissonance between the world as we perceive it to be and the world as we know it to be. Her work has been exhibited in Hordaland Art Center (NO), Astrup Fearnley Museum (NO), Blank Projects (SA) and Palais de Tokyo (FR) to mention a few. In collaboration with Cameron MacLeod she recently opened ALDEA center for Art, Design and Technology in Bergen, and this fall she enrolls in a Ph.D. at The University of Bergen.

Press

03.09.2018

Firda

Eg såg tidleg at ho hadde heilt spesielle evner

Av Geir Ivar Ramsli

07.09, 2018

NRK Radio

Intervju med Magnhild Øen Nordahl, om kunsten og om VU18

Distriktsprogram Sogn og Fjordane

Magnhild Øen Nordahl

The Distance to the Horizon

2016

Video, 26’33’

The video documents the journey from a given point at sea, to the point one could see as the horizon to begin with. The expedition was undertaken in a small boat by the artist herself.

The Light from the Horizon

By Hans Carlsson

Theoreticians suggest that attributes of Modern art, such as the loss of unified perspective and dissolution of homogeneous space, can already be found in works by the romantic painter J. M. W. Turner. Jonathan Crary, art historian, argues that Turner's painting Light and Color (Goethe's Theory) – the Morning after the Deluge – Moses Writing the Book of Genesis (1843) anticipates new technology, such as photography and other visual practices that will emerge later in the 19th Century.(fn.1) The painting, where one can hardly distinguish a sunrise or sunset over a diffuse - possibly stormy or foggy - ocean, destabilizes the very appearance of a horizon, already barely visible. The rules of perspective are disregarded. Rather than representing something ‘out there,’ the painting seems to replicate an inner image, a lasting visual impression. Similarly, in her essay “In Free Fall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective,” the artist Hito Steyerl describes Turner’s art as a violation of the social logic of the geometrical perspective, a logic derived from enlightenment thinking, which imagines a homogeneous Western subject at a privileged vantage point from which to observe the world.(fn.2) The violation which Steyerl identifies in Turner’s work breaks apart the singular horizon. Perspective multiplies and dissolves. This violation lingers in Modern art, along with the development of photography and film, which reaches a new level with advent of artistic video installations.

Such a fragmentation of the space and experience of art is partly, but only partly, discoverable in Magnhild Øen Nordahl's work, which often makes the viewer aware of the possibility to perceive the world from many perspectives. At the same time, however, her installations, sculptures and videos maintain a pedagogical, unified and accessible quality, which emphatically expresses the presence of a common basis for these very different perspectives.

In the video work The Distance to the Horizon (2016) the horizon appears in its normal aspect: fixed and clearly in the middle of the picture, as per the rules of perspective. From a small wooden boat, we are looking toward the line where the surface of the Earth curves and disappears before our eyes, where the blue ocean meets the sky. But, we are moving forward. The boat should – if the horizon were actually a line at the edge of a flat plane – have reached the end of the world before the film’s end.

Anyone might say that the Earth is obviously spherical, and that is why we cannot reach the horizon. But how many of us have actually taken a voyage like that in The Distance to the Horizon? How many have experienced the Earth curve? Most of us are left to trust the experts of the scientific community who collectively decry: the Earth is round.

Modern science follows, in accordance with the philosopher Karl Popper, the idea that knowledge of things is acquired through deduction. The deductive method requires that assumptions must always be subject to analyses and tests from a skeptical position, that what is believed to be right might be wrong. They must be falsified. In this way alone can professional scientists maintain a sobriety and it is only this critical approach that will lead us toward to a correct understanding of the world. The deductive method’s predecessor, the inductive method – usually associated with the 16th century philosopher Francis Bacon – was differently oriented. It was concerned with the collection of knowledge, of compiling a reserve of experience, and then, in order to prove their claims, the scientists were constantly involved in testing their veracity using empirical studies. The two methods have one thing in common: both were based on the principle that scientific results are arrived at through observation and rational analysis; collecting knowledge is mandatory, as is a system for classifying, organizing and analyzing this knowledge.(fn.3)

The central question today may be who has the right – the mandate – to engage with science. The concept of a researcher at a university, institute or company who is adequately educated to perform their task is quite new. In early modern times, scientific investigative research was often relegated to hobby-status, disconnected from economic value or academic status. It's really only since the second half of the 19th century that the position of a researcher has become a profession. Some have warned that the institutionalization of acquiring knowledge actually challenges the basic principle of scientific deduction – why would professional scientists question their own conclusions by submitting to the deductive logic, and thereby run the risk of possibly ruining the safety provided by their professional status?

This is one of many challenges for a science that constantly wishes to refine and critically review its own methodology. There is a tradition in Western humanities of criticizing the language of scientific truths by pointing at the parts of so-called scientific results that rely on highly-ideological assumptions: the paleontologist and science journalist Stephen Jay Gould has remarked on the racist foundations of archeology, theology and anthropology; the philosopher Donna Haraway has pointed out how both masculine norms and anthropological conventions prevent scientific empirical studies in science; and Thomas S. Kuhn has – in stark contrast to Popper – criticized the ability of singular individuals to think beyond the epistemological frameworks offered by a certain knowledge paradigm.

In the exhibition The Frisbee Perspective (2018) at Sogn og Fjordane Kunstmuseum, Nordahl presents parts of the rocket built by “Mad Mike” Hughes, a 62-year-old former limousine driver. The goal of the rocket was to raise money for a larger spacecraft, capable of flying high enough to prove that the Earth is flat. Hughes, who is part of the so-called Flat Earth movement, does not rely on the scientific community collective answer to the question of whether or not the Earth is flat. In an interview published by The Two Way, a blog affiliated with NPR (the United States’ media network National Public Radio), he goes so far as to say that he “does not believe in science, since it's no better than any mythology”. Hughes has his own ideas on how to get to know the world:

I know about aerodynamics and fluid dynamics and how things move through the air, about the certain size of rocket nozzles, and thrust. But that's not science, that's just a formula. There's no difference between science and science fiction. (fn.4)

Hughe's do-it-yourself attitude results in a distrust of the analysis and large-scale collection of information in the service of science. This serves to stress the fact that science, the supposed safe haven of free thought and exploration, in fact limits empirical studies of the world. Hughes can be seen as part of an influential anti-science and anti-information movement, which typically has ties to the populist christian Alt-Right movement, and is perceived as a thorn in the side of many social as well as academic institutions.

Some have pointed out the similarities between this movement’s science criticism and the criticism stemming from within humanities mentioned above. Such a simplified historical dialectical attitude, which could be attributable to the sociologist of science Bruno Latour among others, is problematic in many ways, not least because it corrupts the fact that many of the theorists involved in reviewing and thinking about scientific methodology actually make use of the same critical approaches as Popper argued for. It is a kind of thinking that not only assumes that science tells the truth, but is constantly testing this assumption against criticism of the basic foundations of research by questioning the relationships between facts, perception, ideology and results.

Something similar can be said about the work of Magnhild Øen Nordahl. Her installations often put objects and theories from widely different sources against one another in a clear way, as if each proposal should be observed with the utmost care and examined at their foundations. In the exhibition The Frisbee Perspective, theories regarding the shape of the Earth are illustrated. In a previous work, Occupational Knots (2014), the performances and metaphors that associated with the knot became the starting point. The work consists of a series of sculptures based on knots found in the encyclopedic knot book Ashley Book of Knots (1944): a book of clear lexical ambitions and a somewhat unclear empirical method. In connection with the sculpture installation, the fanzine Pb? Ni? He? presented material from practical as well as mathematical knot-theory. The mathematical knot theory arose from the hypothesis that everything in the world consists of the same material on the nano-level, but is firmly shaped in different ways, as different knots. The theory was eventually replaced by a better-functioning atomic model, and only a century later when scientists discovered knots in the human DNA, it regained interest from fields outside mathematics.

The question is whether the gesture itself – of placing scientifically-sanctioned material in relation to more 'amateurist' attempts to an epistemology – is in fact inline with a deconstructive strategy: to emphasize the value of having different ways to understand the world, while simultaneously studying the power relations between these different ambitions? My answer is that Nordahl's art rather opens up the possibility for simultaneously thinking inside of different thought systems: the scientific deduction, the spirit of an amateur inventor, the reactionary science criticism, poststructuralist antihumanism, etc. When these different systems are side-by-side, one can observe their differences and at the same time recognize that they all have roots in a common world, one that is commonly unwilling to take a thing for granted.

The works in the exhibition The Frisbee Perspective also make allowances for different systems of perception to be placed in an immanent relationship with each other. Previously, in connection with the opening of an exhibition at Skånes Konstförening in Malmö, Sweden, Nordahl answered a question about her interest in different measurement systems, both historical and in present-day use:

I started doing research on body-based systems for measurements such as a stones throw, a days walk, a halt, an arrow shot, a rowers shift all of which were in use in Norway before the introduction of the metric system. (...) What type of effect physical activity, sensory input and culture has on our thinking is being done a lot of research on in Neuroscience at the moment, for instance at Karolinska Institutet where I was following the course ”The Cultural Brain”. Some would say that making use of the body as a source of knowledge is nostalgic or adhering to some trendy mind-body-fitness ideology, but I think it is more about acknowledging how we function as human beings and make use of this when we decide how to do and make things and live our lives.

The constant, never-ending, human conceptualization of the world that Nordahl identifies is based on relations observed in the physical world as they become a part of our mind, constructing of our self and our life. The body is in a cognitive relationship with other bodies in the world; and from this relationship we gain experience and information for use in neuroscience as well as in the establishment of different systems of measurement.

To think of the body in relation to surrounding bodies, natural phenomena and existing technology, involves a changing relationship from which we extract meaning. It is easy to interpret such a relationship as a non-anthropocentric description of consciousness and its relation to the outside world. Many could be called upon in this context (Donna Haraway among others), but here I want recall an important predecessor in the field, the anthropologist and cybernetic Gregory Bateson.

Bateson (1904-1980) worked for his whole life as interdisciplinarian, making revolutionary studies in ecology, psychology and neuroscience. His method always departed from a type of ecological model of thought around social development and evolution. This resulted in, among other things, a critique of ecological miscalculations, where political decisions followed firm beliefs in man's ability to control other beings and the surroundings, rather than of seeing themselves as part of the same feedback system. Bateson’s critique of the prevailing social order, based on his studies of human actions in relation to each other and their surroundings, expanded into active work against fascism. In a 1978 interview with Daniel Goleman for the magazine Psychology Today, Bateson said:

Because we think in transitive terms, we lose the systematic whole. We say that something affects something else: “Dogs Hunting Rabbits”. But if you say “Dog-hunter-rabbit” then you're on your way to a completely different view upon things. (fn.5)

What Bateson points to in this quote is that the relation between the surroundings and human beings is more important than the individual and the surroundings separately. It is possible to see a similar interest in this relationship in Nordahl’s art, which also frequently raises questions regarding the significance of interface – questions about the possibilities and methods now available to model a worldview. This is the case, for example, in her video work, How to Make a Utah Teapot (2016) where the experienced potter Anne-Lise Karlsen makes a Utah Teapot, a standard reference object used in 3D modeling software. The virtual teapot was developed by the American computer scientist Martin Newell in the mid-1970s, and has achieved a unique cybercultural status because of its wide use.

The Frisbee Perspective presents frisbees as 3D-rendered objects which differentiate themselves from the shadows they cast on the wall, as if the form displayed an ambiguity in its readability, pointing out the different directions available to interpretation. In both The Frisbee Perspective and How to Make a Utah Teapot, it is the cooperation between image / interface and observation that facilitates the production of meaning. Objects are anything but passive in this process.

The question remains whether it is possible for humanity to fully embrace this nonanthropocentric posture. But viewers of The Frisbee Perspective can at least try to regard their presence in more relational terms, as only a part of a network in the relation between art, space and perception – or as a “visitor-viewer-exhibition”. We are not alone as observing animals: instead we share the same cognitive space with people, things and course of events happening around us, which are written into our consciousness, regardless of whether they fit into a frame of artistic, scientific, reactionary or philosophical systems.

___________

fn.1. Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century, MIT Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, 1992 (1990), pp 139-142.

fn.2. Hito Steyerl, “In Free Fall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective”, in: E-flux, Journal #24 April 2011. www.e-flux.com

fn.3. Karl R. Popper, The Logic of Scientific Discovery, Routledge: London & New York, 2002 (1935), pp 3-27; 27-209.

fn.4.“The Two-Way”, November 22, 2017. www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way

fn.5. Gregory Bateson, “Att frigöra sig från dubbelbindningen: Gregory Bateson and Daniel Goleman”, in: Erik Graffman ed., Gregory Bateson: Mönstret som förbinder, Mareld: Stockholm 1998, p 122. Translation mine.

Hans Carlsson is an artist, writer and curator based in Malmö. His artistic and curatorial work is focused on archival practices, often with references to knowledge and culture producing institutions such as libraries and museums, and their relationship to technological and industrial development. As a writer he has produced interviews, essays and critique for Kunstkritikk and for Helsingborgs dagblad. Exhibitions and projects include shows at, and collaborations, with Tensta konsthall, Gnesta Art Lab, Arbetets museum and Malmö Art Museum.

Magnhild Øen Nordahl

The Frisbee Perspective

2018

5 Sculptures

130 cm x 60 cm each

XPS, powder coated steel, lamp

Magnhild Øen Nordahl

Opplysninga, Formørkelsen

2018

Sculpture– installation with lamp

Side panels from a home-made rocket built by Mad Mike Hughes in California, used in a mission to prove that the earth is flat. Installed with single wire allowing a rotation creating sporadical eclipses.